Searching through the WHO main website (https://who.int – accessed February 2024), I found an interesting article on the state of the UK health system. […]

The World Health Organization (WHO) was founded shortly after World War II and is the United Nations agency that promotes the attainment of highest level of health care among all nations.

The full publication is available for download at https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/united-kingdom-health-system-review-2022

Reference Number/ISBN: 1817-6119

Part of “Health Systems In Transition” series, Vol.24 No.1

I have summarised the main points and added a bit of context where appropriate:

Life Expectancy

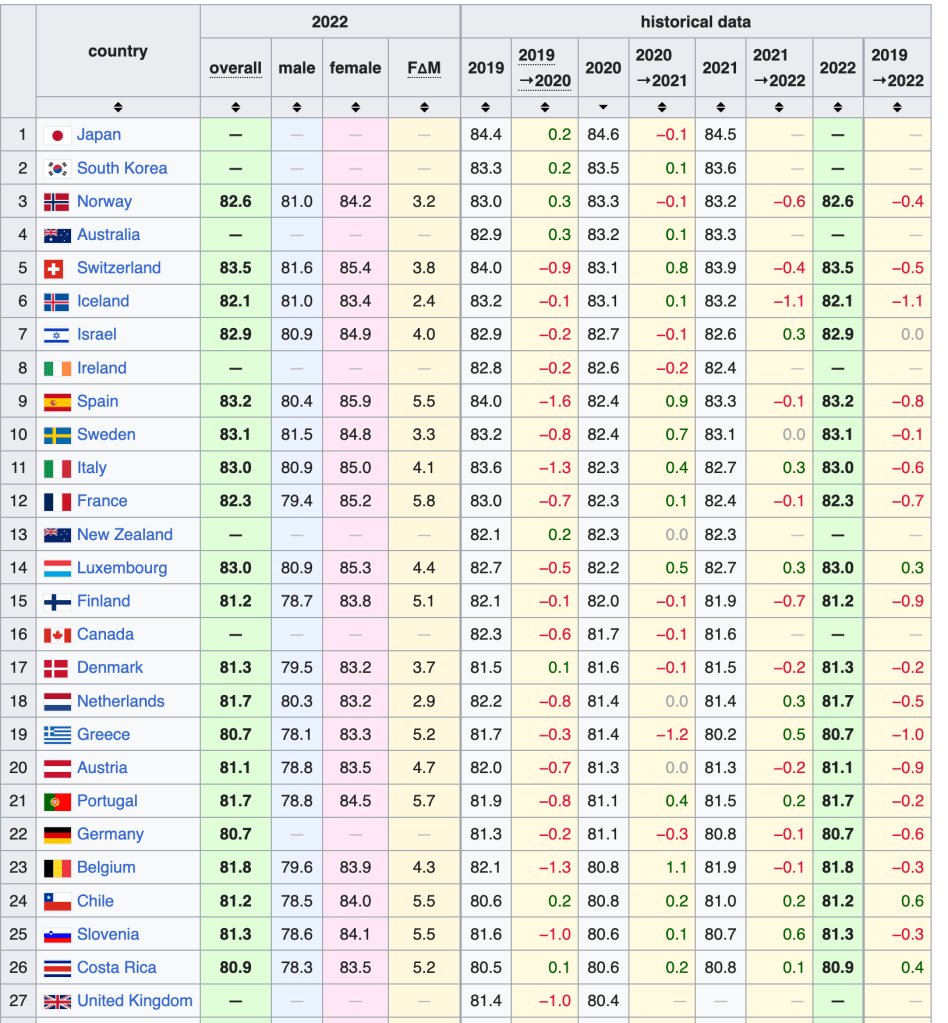

The UK’s life expectancy is slightly above average of EU countries but if we take other similarly high-income countries for comparison, the UK lags behind.

Increases in life expectancy over the past 20 years have resulted in an average of 81.2 years of age for UK residents, which is just above the EU average of 81.1 but lower than countries such as Italy and France.

The WHO report mentions that life expectancy varies between home nations, with English people more likely to live longer than counterparts in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This may be explained by the income inequality that persists in the UK, with “millions of people continually at-risk of poverty”.

Report by Guardian newspaper (dated March 2023): https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/mar/16/life-expectancy-in-uk-growing-at-slower-rate-to-comparable-g7-countries

The following table taken from Wikipedia shows OECD countries sorted by life expectancy in 2020 – source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_life_expectancy :

Four separate health care systems

Access to the National Health Service (NHS) by UK citizens is generally free and based on medical need. The report also mentions that social care services, however, are not always free and access is in some cases means-tested.

Healthcare in the UK has been devolved to the separate governments of the four home countries. The central UK Government allocates a set budget for healthcare in England while each of the other home nations decides what proportion of their allocation from central government is spent on health care.

There can therefore be divergence between health services in different parts of the UK. For example, NHS medicine prescriptions are currently free for people of all ages who live in Wales, regardless of personal circumstances. In England, prescriptions are free in some cases based on age, income and personal medical history; other patients must instead pay a fixed fee for all NHS prescriptions.

Presumably the Welsh Government must have cut back on other, lower priority, services in order to finance free prescriptions.

The following chart shows spending per person in the four home nations (based on a 2016 article so data is slightly old):

Source: https://www.health.org.uk/chart/chart-spending-per-head-in-the-four-countries-of-uk – the Health Foundation (https://www.health.org.uk/) is a charitable organisation.

Financial consequences to patients of UK health system

The NHS is funded mainly via UK personal income taxation, plus out-of-pocket payments in some cases.

This system of financing healthcare and the fact that NHS services are generally available to the public regardless of their personal income, results in a redistribution of wealth “from rich to poor, from health to the sick”.

The UK health system effectively helps to reduce inequality among its population.

Out-of-pocket payments are required for some services included dentistry, optometry, and (as mentioned earlier in this blog) social care and prescriptions in some UK countries. In these cases, the required payment is means-tested.

The following NHS England article discusses the above points in more detail: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/our-approach-to-reducing-healthcare-inequalities/

UK levels of healthcare staff and infrastructure is low

This point is a negative observation by WHO. The UK is quoted to be “exceptional among other comparable high-income countries in that it has relatively low levels of both doctors and nurses”.

The report goes on to observe that the number of hospital beds and diagnostic equipment (e.g. computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scanners) is relatively low compared to other high-income countries.

This in turn leads to high waiting lists for certain health services, as reported frequently in news channels.

The report, I think, is critical of the NHS recruitment policies that prioritise staff levels at hospitals instead of at community-level facilities. Crucially, the UK has an ongoing reliance on foreign health care staff.

IT services

The report mentions how the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the need and distribution of better health information technology (IT) services. I remember downloading apps on my mobile phone for COVID-19 vaccination status and to record my whereabouts.

However, the take up of IT services is not always integrated and varies between healthcare facilities, with some hospitals, for example, still relying on paper notes.

Community care

The report again mentions how hospitals have seen greater investment than community-based facilities. For the vast majority of patients, the first point of contact remains the local general practitioner (GP), who acts as a gatekeeper to NHS services: patients are treated by the GP and local clinics and/or refer the the patients to NHS specialists.

While the overall standard of care is still high, the system inherently results in inequalities in access to NHS services.

Social care is particularly singled out by the report. The devolved governments of the four home countries have different approaches to social care. Some countries aim to create a social care system available to everyone regardless of personal income (i.e. in the same way NHS health services are offered). In England, presumably due to the far larger population and associated costs of providing care, there are discussions on charging patients a fee, capped to a lifetime maximum, to cover the costs of social care.

Final thoughts

I recommend the WHO report to anyone with an interest in how the NHS is funded and how NHS services are provided. I’ve only listed some of the highlights in this blog but the report goes into greater depth, listing sources of information and providing data to justify the analysis.

Some of the points above are well-known to readers who also follow the news. I posted a note on NHS junior doctor strikes in January 2024; if the NHS is experiencing staffing shortages, it would make sense to consider increasing the salary of healthcare professionals to reasonable levels.

A separate, longer discussion is needed on NHS funding and priorities. I wholeheartedly think that having a comprehensive health service that is generally free to access is an enormous benefit of life in the UK. However, it is clear that to offer a world-leading service, investment is required both in terms of funding and political will.

Leave a comment